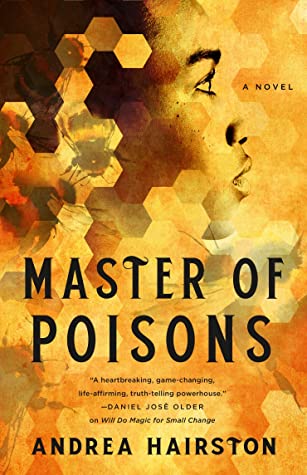

Genres: Queer Protagonists, Epic Fantasy

Representation: Cast of Colour, Queer MC, F/F or wlw, F/NB, NB/NB, several nonbinary secondary characters

Goodreads

The world is changing. Poison desert eats good farmland. Once-sweet water turns foul. The wind blows sand and sadness across the Empire. To get caught in a storm is death. To live and do nothing is death. There is magic in the world, but good conjure is hard to find.

Djola, righthand man and spymaster of the lord of the Arkhysian Empire, is desperately trying to save his adopted homeland, even in exile.

Awa, a young woman training to be a powerful griot, tests the limits of her knowledge and comes into her own in a world of sorcery, floating cities, kindly beasts, and uncertain men.Awash in the rhythms of folklore and storytelling and rich with Hairston’s characteristic lush prose, Master of Poisons is epic fantasy that will leave you aching for the world it burns into being.

I received this book for free from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review. This does not affect my opinion of the book or the content of my review.

Master of Poisons is an epic fantasy where the world needs saving – not from some Dark Lord, but from people who are good but weak, and those who are strong but corrupt. The world is being consumed by poison storms, land and rivers ruined more and more every day, and if something isn’t done…

You might expect this, then, to be some kind of preachy environmentalist book. It’s not. Environmentalism is a huge theme – climate change is literally the Big Bad – but Master of Poisons is a big, beautiful fantasy, with magic and mountains, pirates and politics, questions and the quests undertaken to answer them. Djola, the only one on the Emperor’s council advocating for deep and long-term change as a solution to the poisoned land, is exiled for not having easy answers to give. Awa, a young woman who discovers she can travel to the wondrous otherworld called Smokeland, is sold by her father – and raised by Green Elders, a society of wandering bands who live outside of normal life, keeping the old ways alive and weaving new ones for the future.

And then things get complicated.

This wasn’t an easy book for me to read, and not because of the suffering too many of the characters have to go through. Something Western readers should be prepared for is that Master of Poisons is written in a style that’s more reminiscent of African oral storytelling traditions, and for me, at least, it was a struggle to adjust. But that doesn’t make it a bad book. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about why I struggled so much, and reading about how quick white readers are to dismiss books as bad when they’re written in styles we’re not used to, styles that come from different literary traditions than the ones we’re familiar with. It would have been very easy for me to put Master of Poisons down and walk away, give up on it because it was just too much of an effort. But that would have been wrong, and it would have meant missing out on an incredible book.

The issue is not the writing style. The issue is me, and how little exposure I’ve had to other styles of storytelling, and how little I’ve done to fix that. I hope other readers and reviewers realise the same thing, rather than critiquing Master of Poisons for something that isn’t a flaw.

There’s no denying, however, that the sort of choppy writing style did leave me confused a lot. I’m not sure how much of that might be a genuine flaw, or if I’d have an easier time if I read the book again, but it seemed that things sometimes happened very suddenly, out of nowhere with no warning. Characters sometimes acted or spoke in ways that contradicted what they’d done before, or changed their minds without visible prompting. Revelations sometimes came very casually, so that you might almost miss them. That was difficult to deal with.

But gods, this books is so worth it. It’s beautiful. The world Andrea Hairston has created is just breathtaking, so real I felt like I could walk through the pages onto Kyrie’s mountain, or the Floating Cities. There’s some seriously brilliant worldbuilding, and Hairston never falls into the trap of generalising groups or peoples – not all Green Elders are perfect; not all barbarians are savages; and certainly not all good citizens are actually good. Smokeland, the mysterious, magical realm that can be traveled to by the spirit-body, is dreams and poetry spun into a place you can visit – and that I want to visit! It’s more enchanting than any kind of otherworld or ‘fairyland’ I’ve read about for a long time.

“Throughout the Empire, people are just surviving and so water, air, and earth become poison.”

“What do you know?”

“Denial is worse than poison sand.”

I’ve read some interesting thoughts and essays recently about how we, as a society, focus too much on the idea of heroes, the idea of great revolutions that will magically fix everything instantly. The stories we glorify ignore the fact that change is hard and slow and requires everyone to pitch in – not lie back and wait for a single Chosen One to wave a wand and make everything better. More and more, it’s becoming obvious that we need to hear this – that change is hard, and slow, and requires all of us working together. It isn’t all glory and trumpets and wrapped up by the final chapter.

Master of Poisons is very much a story about real change. Djola and Awa might be the main characters, but they can’t fix the world on their own, and a great deal of the book examines the nameless masses and their complicity in the evils that are being done. Everyone is trying to ‘just survive’, as in the quote above – but if you only care about yourself, you’re damning everyone else. And yourself too, in the end, because none of us can survive alone.

“…be a trickster, beholden to no one, responsible to everyone. Create a new realm for all of us.”

The corrupt power structures need to be purged and repaired, but nothing will ever be fixed if the masses, the normal people like you and me, aren’t willing to change how they live and how they think. Djola’s Empire is being torn apart by stirred-up hatreds – quite a big deal is made about vesons (the nonbinary people of this world) and women tainting magic by touching it with their icky female hands being the cause of everyone’s suffering, even though killing these people obviously does nothing. Hezram, the closest thing Master of Poisons has to a single villain, has gained a huge following by using blood magic to stave off the poison sand – and everyone else is willing to look the other way as he sacrifices children and people from the outskirts of society, because they’ve decided the trade-off is worth it. Because they’re scared and just want to survive.

That’s not good enough.

“I’m the end of a story. You are a prelude to change.”

There’s been plenty of talk about how each generation of humanity shrugs and leaves the problems of the world for the next generation to worry about. Master of Poisons says that’s not how it works. Change is slow; it has to be started now, and the work passed on to those who come after. Cynicism and despair have to be fought; idealism and trust and hope are flames that need to be fed. Nothing can be accomplished by those standing alone; it’s only the bonds Djola and Awa forge with their friends, family, and lovers that get them as far as they do. The generational gap has to be closed; we have to be able to work together.

And that ‘we’ doesn’t just refer to humans. It’s been a very long time since I last saw a story that emphasised the interconnectedness of all living things, but Master of Poisons talks about Animal People, Tree People, and gives voices to rivers. Goats, horses, and dogs are all PoV characters at different points in the book, and the trees stand over all. We’re a part of Nature; we don’t own it. It’s not there for us to use, and using it up just means disaster. And again; Djola and Awa are helped and even rescued by their animal friends multiple times. Master of Poisons doesn’t pretend that a dog thinks just like a human – Soot, Awa’s canine companion, isn’t a human shaped like a dog. But he does have desires and fears and loves like all the other characters, ones that are integral.

It’s considered kind of…what? Cliche? Tree-hugger-y? Cringy? To talk about Mother Nature, to seriously consider animals as people, to genuinely honour the trees and the birds. It’s primitive. But it’s also bloody true. Anyone who’s lived with a dog or a cat knows that they’re people. The geckos in the tank opposite me as I type this have personalities. And while I have no idea if plants think in any way I could ever understand, I know burning down the rainforests ought to be a war crime. I know that overfishing the waters results in starvation, that spilling or dumping toxic materials into the sea fucks with the entire eco-system – which includes us. I know you can overfarm land, that you need to let fields rest so they can recover before you plant the next harvest. I know we have more hurricanes than we used to because we’ve spent too long screwing with the atmosphere.

We need the reminder that we’re a part of the world, not its owners. Master of Poisons is that reminder, and what’s impressive is that Andrea Hairston doesn’t beat the reader over the head with it. This review has turned into a bit of a rant or a lecture; the book does not. It’s an unfamiliar kind of poetry, telling a story we all desperately need to hear.

“Impossible is a word for yesterday, not tomorrow.”

Ultimately, Master of Poisons is a story about not giving up. Djola and Awa – and all the other characters – are given plenty of reasons to quit, to walk away or wall themselves off in what safe places are left. But they don’t. Because they can’t.

We can’t either.

Leave a Reply