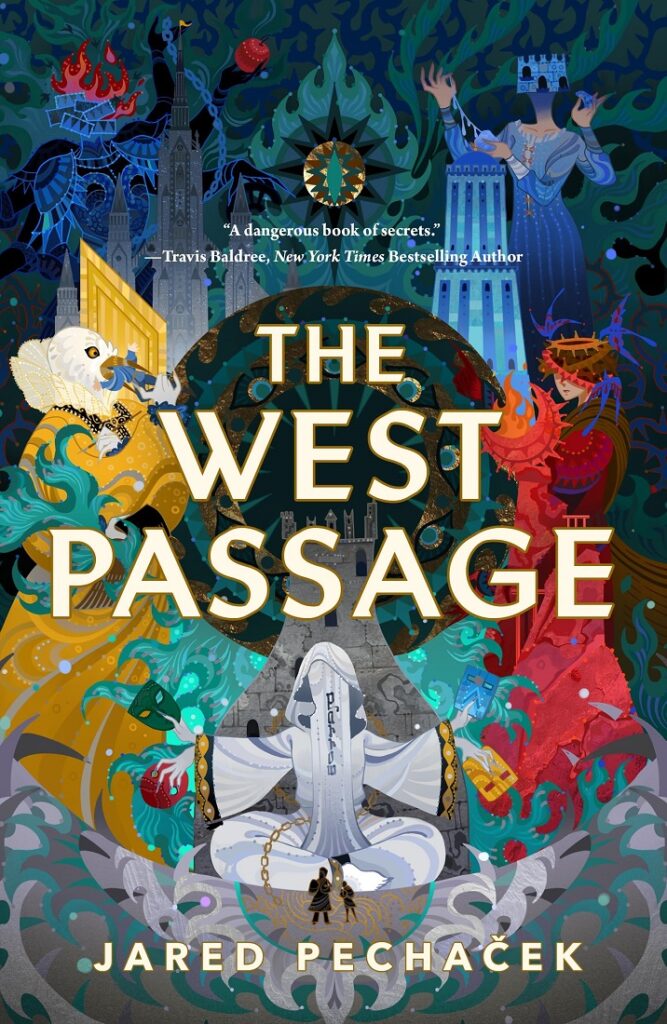

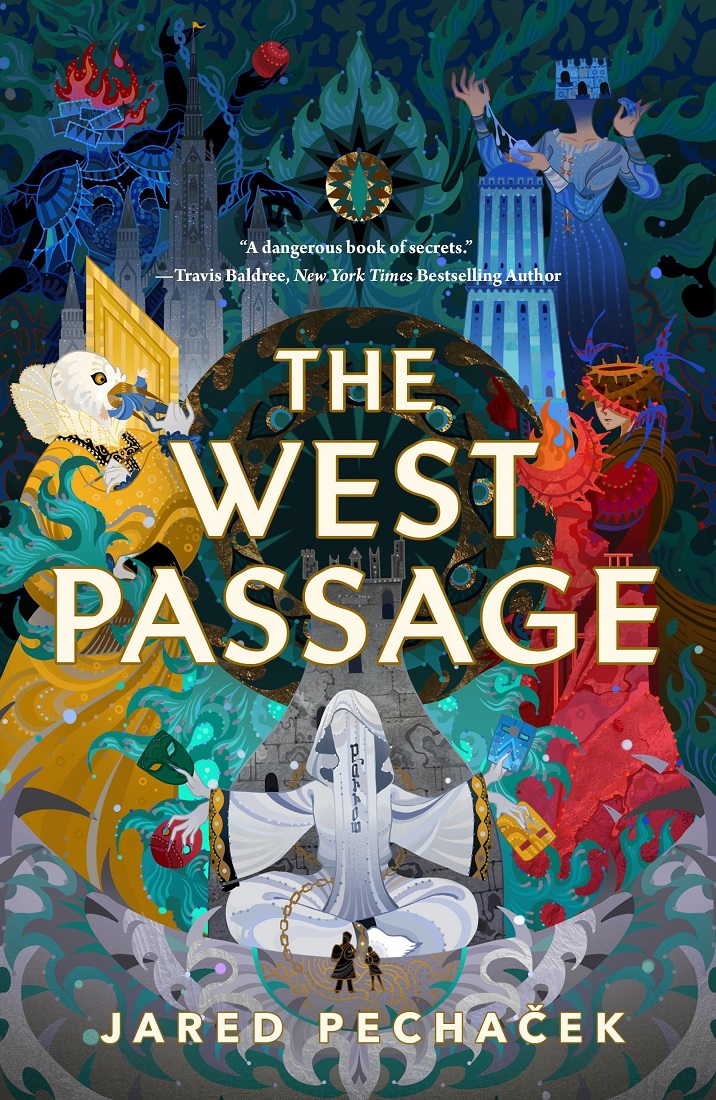

Genres: Adult, Fantasy, High Fantasy, Queer Protagonists

Representation: Gender weirdness (really don't know how else to describe it)

PoV: Third-person, past-tense; multiple PoVs

Published on: 16th July 2024

ISBN: B0CGRZ1JQS

Goodreads

A palace the size of a city, ruled by giant Ladies of unknowable, eldritch origin. A land left to slow decay, drowning in the debris of generations. All this and more awaits you within The West Passage, a delightfully mysterious and intriguingly weird medieval fantasy unlike anything you've read before.

When the Guardian of the West Passage died in her bed, the women of Grey Tower fed her to the crows and went back to their chores. No successor was named as Guardian, no one took up the fallen blade; the West Passage went unguarded.

Now, snow blankets Grey in the height of summer. Rats erupt from beneath the earth, fleeing that which comes. Crops fail. Hunger looms. And none stand ready to face the Beast, stirring beneath the poisoned soil.

The fate of all who live in the palace hangs on narrow shoulders. The too-young Mother of Grey House sets out to fix the seasons. The unnamed apprentice of the deceased Grey Guardian goes to warn Black Tower. Both their paths cross the West Passage, the ancient byway of the Beast. On their journeys they will meet schoolteachers and beekeepers, miracles and monsters, and very, very big Ladies. None can say if they'll reach their destinations, but one thing is for sure: the world is about to change.

I received this book for free from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review. This does not affect my opinion of the book or the content of my review.

Highlights

~beware speech without speech-marks

~names are everything and nothing

~in the midst of surreality, a train

~eldritch is putting it midly

~a most unusual set of bee-hives

:A note: my advanced reader copy did not have the illustrations of the final version! The illustrations make the whole Medieval marginalia thing very obvious, but that’s not how I made the connection.:

There is a castle, of sorts. It is populated with people, of sorts. It is ruled by ladies…of a sort.

A quest, of sorts, is undertaken. Two quests. Because a monster (of sorts) approaches, and the seasons are broken, and much lore has been lost. Even a quest – two quests – may not be enough to save things. Especially when neither adventurer has any idea what they’re getting into.

We’re used to stories of castles and people and quests and monsters. They’re practically commonplace! And yet I beg you to believe me when I tell you that The West Passage is like nothing you have ever seen before. It is the dream a Medieval manuscript might dream, if you gave it enough poppy and absinthe and just a little ecstasy (whether the drug or the emotion is at the potion brewer’s discretion): boldly baroque, casually surreal, full of curlicuing story and powerful honey and illumination(s). It has all the weight of an ancient myth, grand and mostly-forgotten, every detail weighted with meaning that is tantalising, transfixing, unpredictably portentous. It rests upon an extensive, solid framework that we cannot see, but can be sure is there: there is a logic to it all, a way it all fits together, but it is the logic of dreams, a way we can’t quite follow.

We are not meant to understand. Not really. The Ladies do not deign to share their secrets with mere mortals, and why should they?

Wandering here and there were cattle, nibbling at the grass. Their horns were tied with blue and yellow ribbons. Their gills flared and contracted as they breathed.

The actual prose and structure of Pechaček’s debut aren’t experimental; the tale is told linearly, more or less straightforwardly, and readers are not required (or even requested) to perform cerebral gymnastics in order to follow along. You can pick the book up and begin reading immediately without any trouble whatsoever.

But the world Pechaček has created! That is marvellously bizarre, a quietly intense strangeness infused into every element. Cows having gills is the least of it! There are ‘spoon-faced’ people, and the most, um, unconventional bee-hives you will ever encounter, and frogs laying the most incredible eggs. Much of the strangeness is beautiful; some of it is gross or ugly; most of it is neither, only is, and nearly all of it is treated with a matter-of-factness that only adds to the sense of disorientation. It would be so easy for this to have been mishandled, for it to become Too Much, but in Pechaček’s hands disorientation is delicious, addictive, freeing in a way I don’t know how to articulate or explain. Instead of being confusing or annoying or pretentious, the dissonance between how our reality works and how it works in West Passage is intoxicating. I wanted more and more and more of it, and Pechaček didn’t disappoint, showing me wonders and mysteries and miracles everywhere I looked.

A mason bee burrowed into some mortar.

It is not possible to be bored in The West Passage. Especially if you take your time with it, go carefully enough to notice every detail – because the details are, often, mindblowing. Take the quote above: a mason bee?! What is a mason bee?! What do you mean it burrows into mortar?! WHAT?!

It’s very easy to read right past delights like this, because the characters don’t bat an eye at things like mason bees, and so if you’re not paying close attention, you are likely to miss all sorts of treasures; the kinds of things and creatures and people that could only exist in a dream, that make perfect sense until you open your eyes in the morning. One has to approach The West Passage with your sense of wonder bright and fresh and ready to be wowed, but also with one’s magnifying glass ready, slowly examining each and every thing before moving to the next. Because while there is great deal that is front and centre and spotlit, there are even more mirabilia to be found tucked away into corners and between lines – like Medieval illustrations peeking out from behind a capital letter or hiding in the margins.

Making this book both a near-infinite treasury, and a book to be savoured, lingered over as hedonistically and luxuriously as possible.

Potatoes had been set to roast and were taken out for buttering and salting, then browned under salamanders and sprinkled with herbs.

(Browned under salamanders! As in, the little lizard(-looking) fire-elementals!!! This is such a perfect example of how Pechaček mixes the whimsical and mythical and practical at every opportunity.)

To go back to those Medieval illustrations – if you forced me to describe The West Passage’s aesthetic, my answer would probably be Medieval marginalia meets Pliny’s Natural History with a dash of ‘biblically accurate’ angels. If you’re not familiar with Medieval marginalia, then you are in for a bewildering but delightful time exploring it; in the article I just linked, Anika Burgess defines it as ‘from intriguingly detailed illustrations to random doodles, the drawings and other marks made along the edges of pages in medieval manuscripts’. And they can be seriously, seriously weird (and hilariously nsfw), like the inexplicable knight vs snail motif, in which the knight is almost always losing, that can be found all over 13th-14th century books. The Natural History by Pliny (written in 77 AD), on the other hand, is the world’s first encyclopedia (kinda) and is packed full of facts that are definitely not facts – such as the existence of dog-headed people, along with an island of humans who get around by hopping, since they each have only one leg with a giant foot. Put that way, it sounds comedic, and you can definitely laugh at it – but there’s a grandness to it too, a glimpse into a world even more fantastical than ours, dignified in its impossibility. The West Passage reminds me of both; the secretive whimsy of Medieval marginalia, and the solemn strangeness of The Natural History – both orbiting, if not outright emanating from, the terrifyingly unearthly Ladies who definitely echo something of the ‘biblically accurate’ angels imagery.

But just as the Ladies are far more, and far stranger, than rings of golden wheels covered with eyes, The West Passage is a lot more than marginalia plus Pliny. It’s only that that is as close as I can come to describing it to someone who hasn’t read the book. It also, I hope, gives you an idea of how esoteric The West Passage is – or, no, that’s not correct. ‘Esoteric’ suggests that readers with very specific niche interests or information will understand what Pechaček is doing here, and I don’t think that’s true. I saw similarities between bits of West Passage and these interests of mine – but only similarities, not the things themselves. Possibly Pechaček drew a little inspiration from some of these things – I really don’t know – but the result is something wholly original; there are no Easter eggs hidden here for Medievalists (I don’t think), because Pechaček’s world is not built on or out of Medieval marginalia. Nor are any of Pechaček’s creations lifted out of the pages of The Natural History – there will be no spotting a dog-headed person and getting the reference.

There are no references. There are only, here and there, pieces that feel, a little, like things that are almost, maybe, a touch familiar.

But they are not.

It’s another way in which West Passage is like a dream: almost familiar, almost making sense, almost fitting inside your understanding…but fundamentally not.

(And yet, leaving you with the unshakeable certainty that it does all fit together, that it would all make sense to you if you could just…be less mortal. There is an uncanny and eldritch logic to it all – it’s just that we’ll never comprehend it.)

People and things from Grey seemed to belong to the time of songs rather than the time of stories

Like many dreams, The West Passage does not feel as though it started existing only when you discovered it; you may only be entering the story now, but it has been extant for aeons. It’s quite difficult to create a sense of age for a fictional place or culture, but here, it abounds; our merely-mortal main characters are living in the dusty remains of a once-great dynasty, bound by ancient rituals that surely had a purpose once but now have none (or little) beyond the perpetuation of dying traditions. An immense amount of history and other knowledge has been lost – some possibly deliberately – and the waning is obvious in the shrinking number of inhabitants of Grey Tower. The other Towers, which our characters visit during their respective quests, are in very different states, but have still fallen far from the heights of their heydays. What has caused this great decline is unclear, but its existence is impossible to question; Pechaček does an incredible job at making you feel the weight of ages past, and the subsequent weight of responsibility to those vague but vital impressions of past glories. A great deal of West Passage is concerned with this, with the importance but also complete un-importance of carrying on tradition because it is tradition; Pechaček depicts it alternately as despairing, farcical, and irrational – but also as the glue of community, a source of pride, and life-saving. You could read this entire novel as a debate on the value and purpose of tradition, if you like, with the conclusion being something along the lines of: ultimately, it is only by mixing tradition with a willingness to subvert or discard it that we can flourish. Which rings very true to me.

Butterflies moved in and out between the waving tendrils as if among the ribs of a corpse, perching here and there on slim pale limbs. Some of them had court dress on, others wore nothing at all.

The West Passage makes me grateful, all over again, for the word queer, because it’s not nicely, neatly LGBTQ+, but it is undeniably, fundamentally queer. I would be interested (and amused) to see other readers try and pigeonhole or attach labels to the various characters, because they don’t fit into any boxes I know of – and yet many of them, including at least one of our two main protagonists, can’t be called straight, either. The realm of the Ladies has an alien approach to gender, in particular; I don’t want to spoil it, but I was delighted by it (even when I was also confused by it – it’s the good kind of confusion, the kind that comes when you encounter something completely new to you; when your mind has to stretch to accommodate that newness, because it can’t be fit into the way you thought things were before). Yet again, this book makes me think of dreams: gender itself feels like a kind of dream, in Pechaček’s world, and gender certainly has the – the fluidity of a dream, here; impossible to pin down, quickly and completely transforming at a moment’s notice, bound by rules that are immutable in context but make little sense outside of it.

(And yet, can’t the same be said for gender in our world? Gender as a concept? Are the ways in which the Towers determine gender any stranger than the ways we do? Not really, if you stop and think about it. If you’re able to be honest about how little our world’s rules – our rules about almost anything – make objective, rational sense.)

I don’t know if it’s correct to say that gender, and its fluidity, is a major theme in West Passage, but it is important, and it is worked into the foundation of the world Pechaček’s created. The West Passage is queer in so very many senses of the word, and it would be remiss not to mention that, and celebrate that. I don’t know what to say about that aspect of the book, beyond that it brought me joy – but you should know that it’s there.

Hush now, little girl

In the waving reeds

Mother’s gone to fetch the moon

Father’s gone to sow the stars

Sleep now, little girl

In the waving reeds

For the river sings

All the song you need

The West Passage is a journey that cannot be unmade and should not be rushed, that will leave you a little wilder and weirder than you were before, with a new eye or two through which to see the world. It is a chimeric masterpiece full of chimeras of all sorts, majestic and mysterious and maybe mad, splendidly strange, unflinchingly uncanny. It is dream-spun, illuminated, magnificent; unquestionably a treasure of the decade.

It is not to be missed.

What a glorious review. I tagged it at the library to notify me, but I may just have to buy it if they don’t hurry up and GIT IT.

Thank you so much! Honestly, I didn’t come CLOSE to doing it justice – even after reading a library copy, you might find you need one of your own to keep. I know I do!