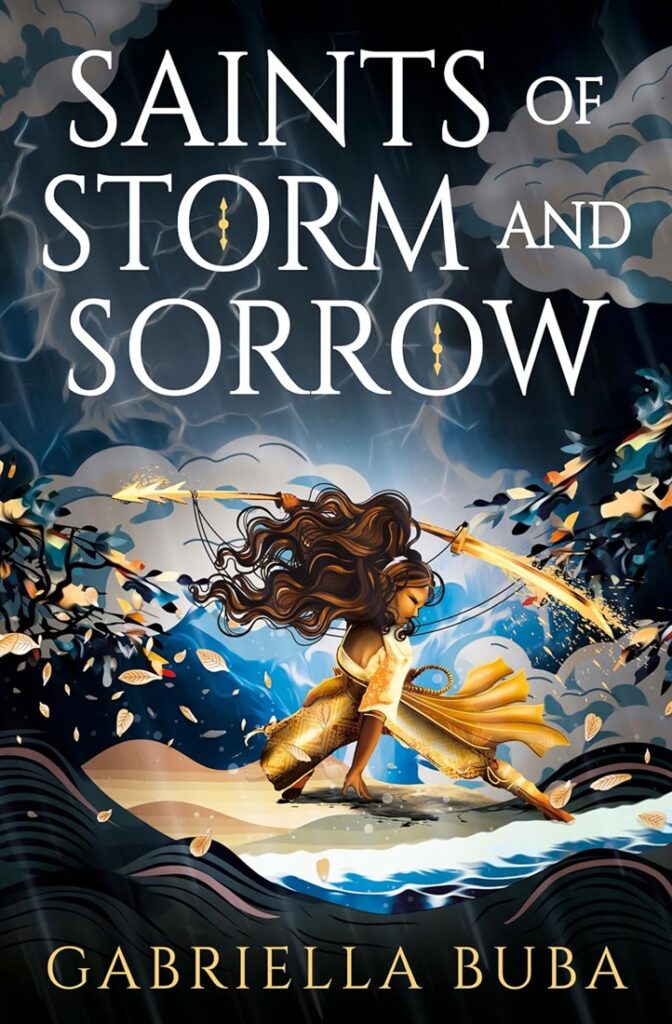

Genres: Adult, Fantasy, Queer Protagonists

Representation: Filipino-coded cast and setting, bisexual biracial MC, sapphic biracial love interest, Filipino-coded disabled love interest, secondary trans character

Protagonist Age: 25

PoV: Third-person, past-tense; dual PoVs

Published on: 25th June 2024

ISBN: 1803367814

Goodreads

In this fiercely imaginative Filipino-inspired fantasy debut, a bisexual nun hiding a goddess-given gift is unwillingly transformed into a lightning rod for her people's struggle against colonization.

Perfect for fans of lush fantasy full of morally ambiguous characters, including The Poppy War and The Jasmine Throne.

María Lunurin has been living a double life for as long as she can remember. To the world, she is Sister María, dutiful nun and devoted servant of Aynila's Codicían colonizers. But behind closed doors, she is a stormcaller, chosen daughter of the Aynilan goddess Anitun Tabu. In hiding not only from the Codicíans and their witch hunts, but also from the vengeful eye of her slighted goddess, Lunurin does what she can to protect her fellow Aynilans and the small family she has created in the convent: her lover Catalina, and Cat's younger sister Inez.

Lunurin is determined to keep her head down—until one day she makes a devastating discovery, which threatens to tear her family apart. In desperation, she turns for help to Alon Dakila, heir to Aynila's most powerful family, who has been ardently in love with her for years. But this choice sets in motion a chain of events beyond her control, awakening Anitun Tabu's rage and putting everyone Lunurin loves in terrible danger. Torn between the call of Alon’s magic and Catalina’s jealousy, her duty to her family and to her people, Lunurin can no longer keep Anitun Tabu’s fury at bay.

The goddess of storms demands vengeance. And she will sweep aside anyone who stands in her way.

I received this book for free from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review. This does not affect my opinion of the book or the content of my review.

Highlights

~no vows of chastity for these nuns

~supporting women’s wrongs 100%

~don’t touch someone else’s pearl (not a euphemism!)

~drown all colonisers

~brace yourself for ALL the Emotions

~a love triangle that is actually excellent

~if she lets down her hair, RUN

Saints of Storm and Sorrow grabs you by the throat and does not let you go for an instant.

It’s also a book where, to be honest, I feel like my main task is just to make sure you know about it – because once you do, it sells itself. A bisexual nun who can summon typhoons by letting down her hair is caught between the goddess she’s hiding from and the totally-not-Spaniards who’ve colonised her home? In a setting inspired by the Philippines?? What else could you possibly need to hear to convince you that Saints of Storm and Sorrow is a must-read?!?

I know, I know, sometimes we get super excited for books with amazing pitches that, in the end, are let-downs. But this is not one of those times. Saints of Storm and Sorrow is every bit as incredible as it sounds. There is no wasted potential here. If I may add a little more alliteration – Saints of Storm and Sorrow is simply superb.

Anitun Tabu herself, garbed in light, the dark moon of her face too beautiful to gaze upon, the black river of her hair a halo lashing in unseen winds. She was crowned in lightning, the spear of heaven’s judgement in her right hand.

“You called my name, Daughter?”

Lunurin is biracial, the daughter of a woman of the archipelago and a Codicían priest – but although she’s spent a good chunk of her life playing a Christian (and therefore Codicían) nun, in her heart she’s anything but. Not for lack of trying; Lunurin works hard to be soft and pleasant, both for her lover and the Church that’s given her a (kind of) sanctuary; she has kept her head down for years, playing the dutiful Christian novice. Behind closed doors, though, she has her romance with Catalina, another biracial novice, with Catalina’s younger sister filling an almost daughter-like role to round out their little family. Interestingly, despite Catalina’s Christian faith being far more genuine than Lunurin’s, Catalina seems to have no shame or complicated feelings about being queer, despite the fact that her sexuality, and her love for Lunurin, go completely against the church’s rules. But in all other respects she’s a good Codicían woman – and very clearly wants Lunurin to be one too.

Lunurin isn’t, though. And not just because she’s a stormcaller – chosen by Anitun Tabu, goddess of the sky and weather, ‘blessed’ with immense power only kept under wraps by the same powerful talisman that hides Lunurin from her goddess. Lunurin sees the hypocrisies and abuses of the Church and the Codicíans, and can’t close her eyes to them; whenever she can, she helps the poor and abused escape the Church’s reach, often with the help of Alon. In Western terms, Alon is basically a prince, the heir of the island’s ruler since his older brother was exiled; he’s also, secretly, one of the tide-touched, able to manipulate salt water with the blessing of Aman Sinaya, goddess of the sea. And he’s the only one who might be able to help when Lunurin and Catalina make a horrific discovery in the early chapters of the book – one that will lead all three of them to the breaking point, and tear them, and maybe even their island, apart.

It took everything in Lunurin not to laugh until she wept. What divine calling could there be when a primordial goddess of the heavens, with lightning for blood and storms at her beck and call, curled under Lunurin’s breastbone, whispering, “Daughter, won’t you drown them for me?”

Drawing inspiration from the Philippines, its history, and its mythology, the setting of SoSaS feels new and unique, a gorgeous and entrancing contrast to the generic Medieval-Europe-esque backdrop that is so confusingly popular in Fantasy. The world Buba has created here is beautiful and intricate, one that I fell more and more in love with the more I learned about it. The people’s relationship to the land and sea and sky, the matriarchal politics, the pearls, the hair, the wildly different (from Christianity) approach to religion, the trio of goddesses whose chosen ones are so integral to the Aynilan way of life… It’s all incredible. No detail has been missed or hand-waved or not-thought-through, with the result that it feels real enough to be a place you could visit it in person if you chose. It doesn’t feel invented, which is the highest praise I can give to a land that doesn’t exist.

For example, let’s talk about mutyas. In the (unnamed) archipelago that Lunurin lives in – clearly a fantasy version of the archipelago that is the Philippines in our world – cultures vary somewhat from island to island (we know that there are hundreds of languages spoken in the archipelago, and in the prologue, we hear of an island ruled by rajs who have tossed out the Codicíans entirely; Lunurin’s island of origin Calilan had a Datu, who was some kind of ruler; and Aynila, which is the setting of SoSaS, has the Lakan who rules the entire island alone, as best I can make out) but mutyas are one of the many things that tie everyone together. A mutya is a piece of jewellery – usually some kind of hair comb for women with magic, but for others it can take just about any form – set with the pearl the person found when they underwent their naming dive. If a person finds a special kind of pearl, it marks them as goddess-chosen – a stormcaller like Lunurin, tide-touched like Alon, or a firetender, depending on the pearl and the goddess. This is a relatively simple piece of worldbuilding, I guess, but for one thing, it’s a beautiful concept, and for a second, it’s woven throughout the entire book. Lunurin’s mutya is one of the things that helps her control (read: suppress) her magic, so it’s something she nearly always has on her person; it’s a sacred, highly personal object that every Aynilan character we come into contact with has and wears, usually openly; by the time we see someone fondle another person’s mutya uninvited, I didn’t need Buba to spell out for me how shocking and violating that was, because she’d already made sure I’d absorbed exactly how important a mutya is. Every concept Buba invents or introduces us to is like that; easy to understand and remember, shown naturally rather than info-dumped on us, and never forgotten or not-followed-through on.

And the magic system! Again, at first glance it looks fairly simple; we have stormcallers who can work the weather, tide-touched who control waves and ocean currents, and firetenders who manipulate heat and flame. But if you look a little deeper, and pay attention, it becomes clear that it’s more complex than that. For example, each kind of magic-user is marked or chosen by one of the three goddesses. We don’t know how or why a person is chosen, but it does seem to be true that the goddesses can’t work their will on the world except through their chosen. For all that she hates the Codicíans, the storm goddess Anitun Tabu can’t destroy them herself – she needs Lunurin for that. Functionally, then, the goddess-chosen are not just the go-betweens between the gods and their people, but literal funnels for the wills of their goddesses. The magic-users are the linch-pin in the relationship between gods and humans; they are arguably that which sustains, and/or allows, the symbiosis between gods and humans. Is that not an absolutely fascinating set-up?!

Not to mention that this is emotion-based magic, tied to the feelings of the person working the storms or sea or fire. Tied, also, to their hair; God can’t help you when a stormcaller lets down her hair, okay? At that point, it’s far too late to run for cover.

“Go to a stormcaller for vengeance, for they do not heal, and they do not save.”

But it gradually becomes clear that all three kinds of magic are actually, also, integral to human life in the archipelago. If the goddess-chosen are the symbiosis of the gods and humans, they’re also what allow humans to live in reasonable balance with the natural world around them. Before the Codicíans came, magic-users didn’t just fulfil important societal roles (the tide-touched were magical healers, which is a whole nother THING that is BRILLIANT but I won’t spoil it for you): the firetenders kept the volcanoes dormant; the stormcallers protected the archipelago from terrible storms; and the tide-touched turned aside tsunamis and carried ships from island to island on magic-made currents. It was never a mastery of the natural world – which would have meant mastery over the goddesses, after all – but it was an elegant system that benefited everyone. The simplicity and genius of that idea? I loved it!

It serves as a powerful, visceral metaphor for the archipelagan way/s of life vs that of the Codicíans, who have come in knowing nothing – and caring nothing – for the islands or the peoples of those islands.

One could use even cage bars to stand.

The Codicíans are, in a word, awful. Not cartoonishly so – if they were, it would be easier to bear. It would hurt less; it would enrage less. But no; these fantasy-Spaniards are painfully believable, as Europeans, as colonisers, as that particularly ugly kind of proselytising Christians. And how to deal with them is one of the central themes, questions, of the book; is it better to submit? To pretend to submit but resist quietly when they’re not looking? To try and compromise with them? To resist loudly? To resist violently?

It is impossible to pretend that this is a question – questions – that exists only within a fantasy setting; to ignore the fact that this is a question that is being asked louder and louder in the real world. It is a question that has been asked throughout history, obviously, but for white readers especially, it is a question that demands an answer right now. (And always.) Because it is generally white people who condemn the violent resistance of minorities and other oppressed groups; it is generally white people who, when pressed, will sometimes admit they understand the impulse to violently resist, but insist that ‘violence is never the answer’. It is generally white people who have no experience, and therefore no true understanding, of what it is like to be the oppressed group. There’s a reason our schools and society hold up and praise Martin Luther King Jr, and ignore or actively decry Malcolm X, and it’s a reason that’s hard to look in the eye if you’re white.

Saints of Storm and Sorrow puts white readers in the place we’ve never been in real life. Buba’s prose is powerful and immersive, creating a story that feels less like something you read than something you experience. I felt everything as if I were inside Lunurin’s skin; the injustice, the insults, the fury, the pain, the desperation, the trying so impossibly hard to be…not good, but good enough; good enough to be valued, good enough to be considered a person, good enough to be safe.

This is as close as someone with my skin colour can get to understanding what it’s like for those in power to see your entire people as less. Sure, my Welsh and Irish ancestors knew oppression under the English – terrible oppression – but not the same kind as this, and I am not my ancestors or in their situation; I in the present day have no idea what that feels like. But Buba conveys Lunurin’s position, experiences, and emotions so well, so intensely, and I’m not claiming that I get it now, but I am saying that this book pulls no punches and sweeps you under and into it, the thick of it, the tangled morass of conflicting desires and needs and feelings that gradually gets simpler and simpler and simpler as the rage burns everything else away – until there’s nothing but the rage left.

How does one deal with this situation? I’ll never know. But Buba puts me in it, as much as anyone can – makes me feel it, as much as anyone can – and then asks: what would you do?

Would you be good – would you be NICE – would you bow your head and take it, all of it, forever? Would you only object politely, quietly, ‘properly’? Could you? Really?

Years she’d made herself small thinking hiding was the best way to protect herself and others. That anything else was too big a risk. But it hadn’t changed the outcome, she only lost a little more, and hurt more deeply, and watched more of her people suffer. She couldn’t keep hoping that if she made herself innocuous enough, she would be safe. Someone would always find her wanting. Like her mother, like her father, like Magdalena and all the sisters of the convent…

Alon is trying, trying to be ‘good’. Standing as a starker and starker contrast to Lunurin as the book goes on, Alon is desperately trying to keep the peace, is fighting so hard to keep all sides happy. Doing what he can to help his people without making waves among the Codicíans (and there’s a point there, maybe a metaphor, about his magic, him being one of the tide-touched and not making waves). He does not think the Codicíans are right or good, but they are powerful, and he is very sure that any violence on the part of the Aynilans will only make things worse. In many ways he’s pretty much the ideal of a ‘good’ oppressed minority, exactly the kind of BIPOC person too many white people think someone like him should be: polite and nice and inoffensive. Not making waves.

But does it help him? Does it help his people? Can he accomplish what he wants by being inoffensive to the offenders? How can he? It’s not sustainable. You can’t have a compromise when one side wants to destroy everything the other is. You can’t protect your people with words when those in power won’t listen; when those in power won’t give you the power to protect them.

What are you supposed to do then?

“Your god can’t help you now.”

And let’s be really clear: the colonisation is not coming from, or fuelled by, just the secular arm of the Codicíans. The Christianity is an equal evil; maybe even a worse one. The Christians are also Codicíans, of course, but their religion is inextricable from the mindset that tells the Codicíans that they are better than the people of the archipelago. Their religion fuels that mindset, reinforces it, validates it. Christianity’s obsession with converting people, with stamping out other faiths, with cannibalising other faiths, is a fundamental part of the colonisation process. This has been true throughout history, and it’s very true in this book, epitomised by the way the Church has stolen and renamed a statue of Lunurin’s patron goddess, Anitun Tabu.

Though Lunurin did not dare speak or even think the goddess’s name for risk of drawing her eye, she knew the statue over the altar was no Codicían saint.

When storms raged and the goddess’s thwarted gaze roamed over Aynila, Lunurin could hear her in the thunder. “Daughter, how can you hide from my sight? How can you let them defile me so? Can’t you see they are erasing me? Won’t you call me by my true name?”

Like: Jesus was a pretty cool dude. I dig him, even if he was weird about a fig tree that one time. But Christianity as practised, particularly as practised during this period of history, is immensely fucked-up. Are there Christians who are good people? Plenty! But baked into Christianity is the idea that non-Christians are, at best, flawed, and we can’t gloss over how that fuelled (and still fuels) colonisation and oppression. And even when the religious beliefs are good, the power structure of what is now the Catholic church – like many power structures – allows terrible people to flourish; it arguably encourages members of that structure to become terrible.

[This is where I initially wrote a rant on all the ways the Catholic structure/system is fucked, but I’m here to talk about an amazing book, not Catholicism, so instead of getting side-tracked let’s just take it as read that I have receipts and the Catholic power structure is deeply dodgy on its best day.]

And honestly, I am glad that Buba doesn’t try to gloss over this, or give the Church a pass. Nope! Nope, no way, nuh uh, we’re not fucking doing that. Besides, it would be deeply strange to explore colonisation in a Philippines-stand in and not acknowledge the harm Christianity did and does in that part of the world and literally hundreds of others. It was a huge Thing. Feel free to read up on it.

For Lunurin, the Church not only wants to demonise her for her non-Codicían ancestry (or kill her for her magic, if they discover it); they also belittle her and dismiss her as a woman, and again, that’s something that is baked into Catholicism. I will, again, not write you another rant essay. But I will point out that fervour with which the Church hunts indigenous ‘witches’ and the fact that the majority of goddess-chosen are women (including trans women!) are extremely unlikely to be unrelated.

(Aynila’s matriarchal culture, powerful elemental magic wielded by women, a pantheon of goddesses… Of course the Codicíans and their Church are determined to crush this culture, these people. Of course they are. It’s not just that they see Aynilans as lesser; the Aynilan way of life is an active threat to everything the Codicíans believe to be good and natural.)

What I’m saying is, the Church is Lunurin’s enemy. It’s the enemy of the whole archipelago, and certainly its goddesses. It’s not just the Codicíans that are the enemy; it’s also the Christian god – or at least his representatives on Earth. There’s no pretending otherwise.

Lunurin did laugh then. The ache of it was grounding. All of her hurt. Her time in the cage made it impossible to swallow her bitterness. “Yes, I’ll apologize, like the last three servants he had caned and caged till their backs festered. What shall I apologize for–my blood? My mother who seduced a priest? Shall I beg his pardon for being a soulless water witch?”

Saints of Storm and Sorrow is very much a story about colonisation and oppression, and examines those things from all angles – the racism and the misogyny, the role of the Church, the Aynilans who side with the Codicíans for power (not realising that the moment they sell out, they’ve lost all power). It’s a book that looks at the different ways to resist these things, the question of which way (if any) is good or best; it looks equally at the whys and the hows. Buba doesn’t simplify or water any of it down for us; these are complex, ugly, many-layered issues, insidiously working its way into every aspect of the story, every facet of the characters’ lives. It’s not as simple as Aynilans good, Codicíans bad; as mentioned, there are Aynilans, especially those in the structures of power, who are all too happy to work with the Codicíans. Nor are the Codicíans a monolith; they have their own internal politics and shifting balances and power struggles. From some angles, it’s plenty complicated.

If you look at it head-on, though, it’s really not complicated at all.

“Ten years I’ve humbled myself. I have cut myself down and swallowed every offending sliver. The time for that is past.

Buba has chosen every detail of her world, and most especially her characters, very carefully. Everything about Lunurin, Catalina, and Alon has a wealth of symbolic meaning for us to ponder (if we choose – you can just as easily allow the story to sweep you along without analysing every little thing, but if you DO enjoy analysing it all, there’s plenty of food for thought). For example, Lunurin is not a native of Aynila – she was born on another island. This feels subtly important. The Codicíans, after all, are not natives either. But Lunurin considers Aynila her home; she considers its people her people. The Codicíans do not. The Codicíans do not even consider Lunurin a person, not really, despite her Codicían father – and sure, some of that is because she’s a woman, but most of it is because she is not white, not white enough – only half, by blood, and not at all in her heart. Her Codicían blood has granted her some security and some measure of privilege for many years, but she is still less, to them.

Catalina is biracial too, and just as Lunurin and Alon stand in opposition when it comes with how to deal with the Codicíans, Lunurin and Catalina are opposing examples of being biracial in this context. Even in the beginning of the book, when Lunurin is still playing at being a good little Codicían nun, she is playing at it. Whereas Catalina, as becomes clearer and clearer, is not playing; she means it, all of it, wants more than anything to be Codicían, to be Codicían enough. Lunurin embraces the archipelago; Catalina refuses to acknowledge that side of her heritage at all. Thus do the politics of their peoples worm their way into Lunurin and Catalina’s romance, because…well, of course they do. No spoilers, but I thought Buba handled that wonderfully, realistically, all-too-believably. I’m very curious to see what other readers end up thinking of Catalina.

Personally I want to fire her into the sun, but ymmv.

And where the two women are both all-or-nothing when it comes to their respective positions, we have Alon kind of in the middle: not agreeing with the Codicíans, and having no desire to assimilate, but trying to walk a line, hold the line, between the Codicíans and his own people.

The three of them form a love triangle, yes, but it’s this other triangle – I don’t know whether to call it philosophical, or political, or what – that is much more interesting to me.

Aman Sinaya preserve him, she even smelled good. The floral sweetness of the sampaguita garlands mingled with the nuttiness of her hair oil. He decided the better part of honor was not breathing.

That being said, the love triangle? Is actually pretty great. I generally don’t have very strong feelings about the romantic arcs of the stories I read, and I actively dislike love triangles unless they end in polyamory. But – probably because Alon and Catalina represent such different stances in and approaches to the world they live in – I actually got so invested in this one! Part of this is Buba’s super-immersive prose, which I’ve already mentioned; but the biggest part of it is…how do I put this? Is: the different expectations, even demands, that Catalina and Alon each place on Lunurin. The different shapes she has to fit into for each of them, and Lunurin’s struggle – though ‘struggle’ doesn’t feel like the correct word – to figure out and accept what her own, real shape actually is. The way this pushes her to push back against both Alon and Catalina’s expectations (and demands), and how intimately this is tied into her growing desire to push back against the Codicíans. It’s a love story that is inextricably tied to the politics of her world, and that is extremely cool to me!

The love triangle is also a very important catalyst for Lunurin’s…I think we can call it growth. I’m a bit worried I’ve given the impression that she’s a swoony, useless kind of heroine: she isn’t. She is fiery, passionate, full of anger – it’s just that she has been keeping that side of herself suppressed for a very long time (for very good reasons!) But while it’s events that lead her to stop suppressing her rage and power, it’s her relationships with Catalina and Alon that teach her that she doesn’t always have to be the strong one, the powerful one. That softness does not cancel out strength. That it is very okay to lean on people when you need to. She has to re-figure out what romantic love really is, but more vitally, she also has to learn how to love herself – including the magic she was raised to see as bad and dangerous; including the rage; including her vulnerabilities, and the (perfectly natural!) need for support and care and kindness.

She cried without worrying how high the river would rise, or if anyone’s roof was leaking, or if she’d start a mudslide. She wept without fearing her unspooling power would draw her father-in-law’s or the Codicíans’ wrath.

I’m making it all sound very Hallmark-y, but it’s not. It’s not.

(And also, I am HERE for men who absolutely worship the women they’re in love with. Alon gets a lot of things wrong, but he gets All The Points for being completely heart-eyes at literally everything Lunurin does – including when she’s being terrifying.)

“Yes.” The word was a growl.

He kissed her again, fervent as worship. “Yes.”

He kissed her a third time, gentle as silk. “Yes.”

I expected to love Saints of Storm and Sorrow; I was not expecting to feel as if I living the story, going through all of it myself. I didn’t expect to feel so much, swinging from fury to panic to delight constantly. I wasn’t expecting there to be so many layers of meaning woven into the tiniest of details. I wasn’t expecting a book that would place feminine rage and power front and centre. I had no idea I would fall for this world, and these characters, as hard as I did.

It’s phenomenal. I can’t believe this is a debut novel, and I can’t wait for more: for more people to read this and love it and scream about it with me; for the sequel, of course; and for anything and everything Buba writes in the future.

REMEMBER THE NAME GABRIELLA BUBA, MY FRIENDS. REMEMBER IT.

(And go preorder Saints of Storm and Sorrow already!!!)

Leave a Reply