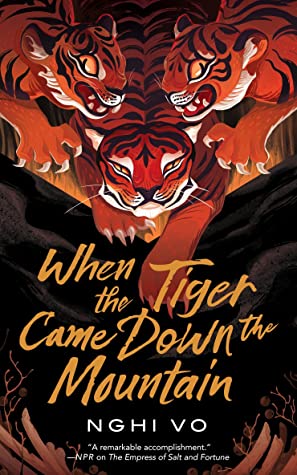

Genres: Queer Protagonists, Secondary World Fantasy

Representation: Nonbinary MC, sapphic main, F/F or wlw

Goodreads

"Dangerous, subtle, unexpected and familiar, angry and ferocious and hopeful. . . . The Empress of Salt and Fortune is a remarkable accomplishment of storytelling."—NPR

The cleric Chih finds themself and their companions at the mercy of a band of fierce tigers who ache with hunger. To stay alive until the mammoths can save them, Chih must unwind the intricate, layered story of the tiger and her scholar lover—a woman of courage, intelligence, and beauty—and discover how truth can survive becoming history.

Nghi Vo returns to the empire of Ahn and The Singing Hills Cycle in this mesmerizing, lush standalone follow-up to The Empress of Salt and Fortune

I received this book for free from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review. This does not affect my opinion of the book or the content of my review.

Highlights

- Story-collecting nonbinary monk is back!

- Mammoths are sweethearts

- Tigers are not

- But they make the best wives

- Forget 1001 nights just get us through this night

- Every version of a story is true; every version is wrong

Nghi Vo blew everyone away with the first novella in this series, Empress of Salt and Fortune, which was published early last year. When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is a standalone story set in the same verse with some of the same characters – and is every bit as wonderful as its prequel.

As with Empress, the premise of Tiger is superficially simple: Chih, the they/them cleric we met in Empress, is telling a story. But it’s not simple at all, because the tigers who are listening keep interjecting, and correcting, the terribly inaccurate version Chih knows.

It’s a story about a tiger, you see. A tiger and her human wife.

But that’s not really what the novella is about. When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is much more about the nature of stories than it is about any one particular story – even if the one Chih and the tigers are swapping is a delightful tale indeed, with snark and an accidental marriage and treasure and careless rescues.

Because what it comes down to is this: Chih knows one version of this story, and the tigers know another. The events being told really happened – there really was a proud, fabulous tiger who married a human woman some time before the novella starts – but humans and tigers have two different versions of how it all went down.

Which one is right? Are either of them right? Or is the truth somewhere in the middle? Another, more wishy-washy writer would have gone with that – the truth is in the middle – but Vo doesn’t give the reader a nice pat little answer like that. We’re not told who’s right, or where the truth is. It’s up to us to decide.

And honestly, which of the two versions are correct matters far less than the fact that there are two versions. That seems to be the central message or lesson or point of Tiger – stories change depending on who is telling them. On who they’re being told to. And that would just be an interesting quirk if we were talking about, say, a fairytale – but the story Chih and the tigers are comparing is history. You’re supposed to be able to trust history. History isn’t supposed to be a story, it’s supposed to be fact. Which means there shouldn’t be different versions of it. You can’t change the past; it’s already happened. It’s not up for debate!

Well, that part’s true: the past is impossible to change without some kind of time machine. But history – well. History is just a record of the past, isn’t it? Haven’t we all heard the saying that ‘history is written by the winners’?

The past is an objective fact. What we remember – what we’re told, taught – about the past? Is not.

Vo doesn’t beat us around the head with this, because she’s far too good a writer for that. Instead she delights us with a story of a fierce, proud tiger-woman and a poor scholar, and alternates between the version humans remember, and the one told by tigers. She doesn’t have to tell us that stories change with the agenda of the teller; instead we see how, in the human version of the story, Ho Thi Thao – the tiger – has the skin of her mother, whom she murdered, hanging above her bed. But in the tigers’ version, it is the skin of He Who Leaps, killed long ago by Ho Thi Thao’s grandfather.

So the human version casts Ho Thi Thao as a matricide, vindicating the belief of humans everywhere that tigers are dangerous and terrible. Whereas the tigers’ version…well, it does say she’s dangerous and terrible, but for the tigers it’s a compliment, and regardless the difference in the bed-hangings is fascinating to me.

And it’s a whole ‘nother level of fascinating because Ho Thi Thao did kill her mother, according to the tigers – she just didn’t keep her mother’s skin over her bed. So the human version tries to cast her in a bad light…by making up something that she actually did. There are levels and levels of knots to analyse there.

One more point I want to make about this is one I’ve never considered before. I took history for my GCSEs and A Levels in the UK; it was drummed into us that no source could be trusted uncritically; everything had to be dissected for its motivations and conscious or unconscious biases. But Vo makes a point my (white, British) teachers never did;

“It is the only version of the story I know,” Chih said. “Tell me another, and I’ll tell that instead.”

“Or you will keep them both in your vault and think one is as good as the other,” said Sinh Hoa, speaking up unexpectedly, her voice gravelly with sleep. “That’s almost worse.”

Reading When the Tiger Came Down From the Mountain, this exchange was a galaxy-brain moment. Because which has more value – an outsider’s record of what happened? Or the record of the people themselves? Is a British army captain’s account of what India was like under British rule of equal worth to records written by the people of India? If a Swedish historian writes about Sami rituals, is that of equal value to what the Sami themselves write about it? Or to bounce back to Britain, should we present what the English wrote about the Great Famine of Ireland alongside the records of the Irish themselves?

It’s not that outsider accounts don’t have any value. But surely they’re not as valuable as, for lack of a better term, insider accounts?

Erasing or ignoring insider accounts is worse, as Sinh Hoa says in Tiger. But when you stop and think about it…there is something really awful in saying that insider and outsider accounts are worth just as much as each other.

Isn’t there?

And maybe Sinh Hoa is being a little unfair here, because after all, Ho Thi Thao’s wife was human. Humans are a part of this particular story, and they have a right to record it too. They have a right to their version.

…Don’t they?

I’m not sure. Especially because, in this context, tigers feel like a proud but oppressed/minority group to me – humans do hunt them, after all, and there are a lot more humans than there are tigers.

So maybe the human version is the outsider version. Maybe it’s not as trustworthy or valuable as the tigers’ version. Maybe they shouldn’t be kept side-by-side in the vault, and considered equally important.

I’m not sure.

But I know that, as well as making me swoon with what’s rapidly becoming her trademark gorgeous prose and entrancing me with the story she’s told, Vo has also left me with a lot to think about.

Great review, I’m so excited to try this book after I loved the first one. I was curious what it would be about, but I didn’t think human-tiger marriage would be it, so interesting.

Thanks! 😀 I had no idea what to expect either, but it turned out wonderful!