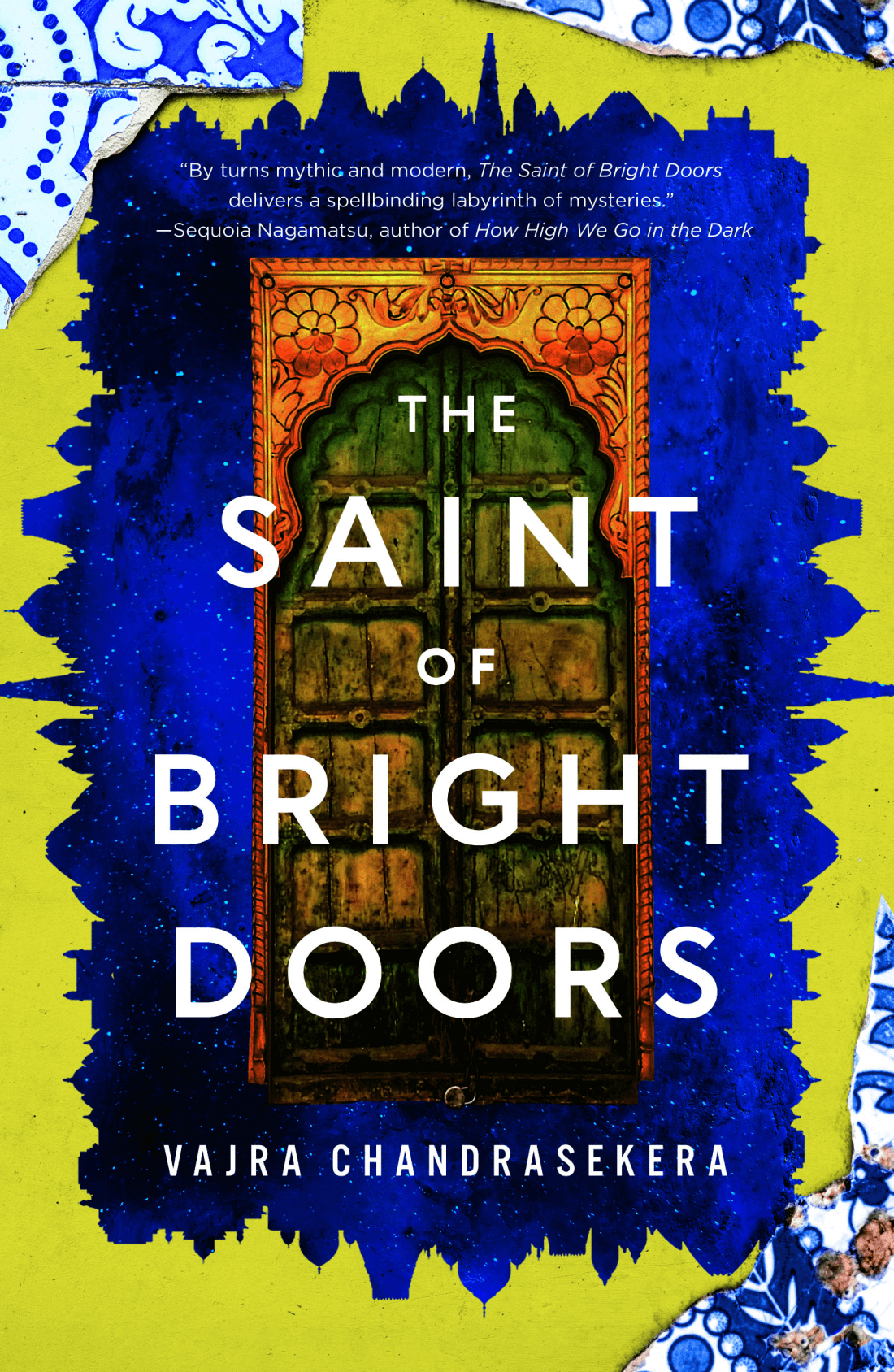

Genres: Fantasy, Queer Protagonists

Representation: Brown cast, bi/pansexual MC, M/M, minor nonbinary characters

PoV: Third-person, present-tense

Published on: 11th July 2023

ISBN: B0B9L229QW

Goodreads

Nestled at the head of a supercontinent, framed by sky and sea, lies Luriat, the city of bright doors. The doors are everywhere in the city, squatting in walls where they don’t belong, painted in vivid warning. They watch over a city of art and avarice, of plagues and pogroms, and silently refuse to open. No one knows what lies beyond them, but everyone has their own theory and their own relationship to the doors. Researchers perform tests and take samples, while supplicants offer fruit and flowers and hold prayer circles. Many fear the doors as the source of hauntings from unspeakable realms. To a rare unchosen few, though, the doors are both a calling and a bane. Fetter is one of those few.

When Fetter was born, his mother tore his shadow from him. She raised him as a weapon to kill his sainted father and destroy the religion rising up in his sacred footsteps. Now Fetter is unchosen, lapsed in his devotion to both his parents. He casts no shadow, is untethered by gravity, and sees devils and antigods everywhere he goes. With no path to follow, Fetter would like to be anything but himself. Does his answer wait on the other side of one of Luriat’s bright doors?

I received this book for free from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review. This does not affect my opinion of the book or the content of my review.

Highlights

~a support group for UnChosen Ones

~messiahs who really deserve murdering

~pearl-divers

~far too much paperwork

~a Very Deadly wisdom tooth

2023 seems to be the year of the baffling but amazing masterpiece; this is the second book I’ve read so far this year that has confused but amazed me.

BY ALL MEANS, KEEP ‘EM COMING!

The moment Fetter is born, Mother-of-Glory pins his shadow to the earth with a large brass nail and tears it from him.

The Saint of Bright Doors is more than a little tricky to summarise. It starts in a reasonably familiar mode, albeit with its own beautifully unique flavour; a young boy with supernatural abilities is trained as an assassin, raised to kill his distant, powerful father. Ah, yes, we think, settling in comfortably. We know this story! Let us embark upon it again, as retold through Chandrasekera’s eyes and hands and voice.

Well, my darlings, this is not, in fact, that story. At all.

Because when Fetter gets to the big city, he just…stays there. Makes a quiet little life for himself. A boyfriend; a support group for other UnChosen Ones; helping out immigrants with their paperwork. He loses interest, and belief in, any great destiny of his own. After the, ah, unique way he was raised, he just wants some peace, to be normal, keep his head down and not make waves.

He has put away childish things. His mad, violent childhood; the indoctrination; his training as a child soldier in his mother’s war against his father: these things, these people are in his past.

He ends up Involved anyway.

I’m honestly astonished by how much Chandrasekera manages to pack in to under 400 pages. It’s as though an 800 page doorstopper has been distilled down to its purest and most potent possible form; nothing is rushed, everything has as much space as it needs, but it’s all so concentrated, powerful, especially coming at us through Chandrasekera’s prose, which grabs you by the throat like a garotte. I read the entire book in 24 hours, ravenous for every word, and I can tell it’s going to be a long time before I stop thinking about it.

This is a book that is equal parts about magic and fascism; about supernatural doors that can’t be opened and the weaponisation of organised religion; about devils (sorry, I mean laws and powers) and the inherent, inextricable violence of colonialism. And the thing is, I’ve read books that deal with these topics before (okay, maybe not the doors) but this feels very different, somehow – less cinematic, maybe, more human, messier, more difficult. The Saint of Bright Doors is not the story of a hero either creating or joining the resistance, and neatly cutting off the head of the snake in a dramatic climax; it doesn’t follow the pattern we’re used to, and Chandrasekera uses that to shock us open to a very different way of doing things. This is a book that plunges the reader into a state of dreamy dissonance in which anything and everything seems possible – and is.

I don’t know how to put it better than that.

Because if I try and actually explain The Saint of Bright Doors to you, it really sounds like it shouldn’t work. There’s so many threads, and none of them follow the tropes and conventions we reflexively expect; which should be jarring, but in the shocked dream-state Chandrasekera puts the reader in, it’s instead easy to just go with the flow the story, despite it being so unfamiliar in its bones. The characters are not who we expect (and want?) them to be either; Fetter in particular, as he has no interest in being a hero, doesn’t burn with passion to make things better or stop the evils being perpetuated by his father and said father’s followers. What do you do with a main character like that, in a story where terrible things are happening? Isn’t he obligated to join the resistance? Isn’t that where the story is? What’s going on?

It is obvious they fear infection, but infection by disease or ideas or identities?

I can only tell you that it all makes sense as you read it. This is very much one of those you had to be there things – The Saint of Bright Doors is a book you have to read to understand. But that shouldn’t be a problem, because despite what I’ve said it’s easy to read; the pages fly by. Fetter may not be the hero we want, but what he is is an immensely sympathetic (and relatable) twenty-something who doesn’t know what to do with his life, and is just trying to preserve it in the midst of chaotic horror. He’s so easy to understand, to empathise with; the lack of cinematic High Drama is what makes him read so real. There’s a particular, pivotal moment where he Does A Thing that makes no sense at all – but it makes no sense in such a completely human way. I’ve been in that same daze, where you keep walking forward even though you’ll never be able to explain to another person why you did; it jolted me, to see that state of mind captured so perfectly on the page. Fetter isn’t a hero because he’s a real person, and honestly, that makes for better reading.

And my gods, the magic! The supernatural aspects of this story feel both unique and raw; not raw in the sense of unpolished but in the sense of wild, aching, real-and-unpretty. Undomesticated, which is a word I’ve never used to describe magic before but fits so perfectly here. I’ve never read a fantasy where the magical elements felt quite like this; so strange but so believable, impossible but obvious at the same time. Just the fact that we have a support group for UnChosen Ones makes me want to shriek with delight, not (just) because that idea is so damn cool but because all of these people come from different, contradictory faiths that are despite that all equally valid – as evidenced by the fact that Fetter is far from the only one with magical talents. HOW DOES THAT WORK? HOW CAN THE PATH AND THE WALKING AND THE MAN IN THE FIRE ALL BE REAL AT THE SAME TIME? Gah!

(Do not expect an explanation. You will find no hard magic systems here.)

The bright doors are not locked. They are not even closed. The bright doors of Luriat are wide open.

The way the supernatural elements were braided into the fascism honestly stunned me – the more I think about it, the more impressed I am, the more I adore Chandraseker’s worldbuilding and twistiness and weird brilliant mind. But one does not, obviously, adore the fascism, and I’m not sure I’m smart enough to talk about this properly, to fully appreciate what Chandrasekera did here. We’re shown a supercontinent (not a world) being battered and burned by pogroms and war, fuelled and incited by the twin sects of the Path Above and the Path Behind, and it is horrifying without being nightmarish, somehow. We see mass executions and people being burned alive, but in that state of dreamy dissonance Chandrasekera has created it is possible to look at these things without flinching – and I think that’s the point.

Let me put it this way: usually, I skim or skip over these kinds of scenes. I simply Cannot. But Chandrasekera let me – made me? – look, and I think there’s something important in that, even if I can’t quite put into words what or why. Maybe because – flinching, and looking away, is…well, cowardly? We flinch away from these same horrors in the real world far too often; we prefer not to see, not to know, not to think about it. Chandrasekera doesn’t give us that option, hypnotises us into looking and seeing, while simultaneously making us able to see. Not by making it less horrifying, but by making us able to bear looking at it. Because we should look at it.

Do you see?

What I want to do, ultimately, is to break the cycle in which plague and pogrom for the segregated, disaggregated many lead to power and profit for the few. At least for a little while. I want to show people that the death and the loss we’ve learned to accept are neither a curse to be borne nor a price to be paid, but are the efficient functioning of Luriat, working as designed.”

One thing I do want to note is how well Chandrasekera captures the horrifying absurdity of fascism, something I don’t think I’ve ever seen fiction do before. There’s a bleak humour to the endless lists of governmental factions and departments, a ‘you have to laugh or you’ll cry’ weight to Fetter’s inability to keep straight all the different police and military death-squads. It’s not comedic, but it highlights the despairing wtf of the rational mind being confronted with irrational hate; how the reasoning is so bad it should be funny, would be funny if it were, you know, not about genocide. I can’t think of another book that points out that not only is fascism evil, it’s fucking stupid; that you can’t have fascism without impossible-to-comprehend levels of stupidity.

(Alas, not the kind of stupid that means unorganised, or unable to achieve its objectives. If only.)

And I appreciated, honestly, that none of the cast make any bones about the fact that fascism cannot be overthrown peacefully.

the power of rulers is always based on death magic, and you can’t topple that without violence.

This is a weird, wildly imaginative debut that bids you leave your expectations at the door; your prior experience with the fantastical genre will not help you here. There are layers upon layers to this story, and yet I promise you, it is not a dense, heavy read; it is more than a little surreal, and subversive, and strange, and I love it. The Saint of Bright Doors is a shooting star, coming upon you with no warning and full surprise to dazzle you dizzy. It is not fun, but it is impossible to put down and dear gods is it good.

If it doesn’t make all the Best of 2023 lists come December, it will be a crime.

It’s out next week. Don’t miss it.

Ah! Cassandra Khaw recommended this book at a Barnes and Noble panel. This definitely heightens my interest even more!

I suspect you will DEEPLY appreciate its weirdness!

Your review makes me want to pick up the ARC I was sent and to start reading it immediately (which, I will very soon)!

Also, I can recommend a “weird” book for you! You probably already know which one it’s going to be!

I hope you do, it’s so great!

??? Please tell me more!

Have you heard of “Vita Nostra” by Marina and Sergey Dyachenko?!

I have! I think I gave it a try when it was first released, and didn’t quite get along with it.